The above quotation from Orwell's 'Down and Out in Paris and London' has stuck with me ever since I first read the book. At the time of that initial reading I was working at a branch of that roadside restaurant made popular by the rotund yet diminutive chef; the uniform came in L, XL and XXL and I was (and still am) none of those things. It was a sorry state of affairs, one I used to romanticise by imagining myself to be a Parisian Plongeur rather than a coffee monkey in a ridiculously over-sized nylon shirt. In the memoir Orwell elevates the mundane and often depressing life of those at the fringes of society into something noble and even at times beautiful. The reality (in a Little Chef on the A34 between Oxford and Northampton)was a little different.

Despite learning this lesson many years ago this quotation fluttered into my head this week as I stood in the queue at the Co-op clutching some Jamaican Ginger Cake and a couple of onions (read from this what you will) after a particularly grueling day at work. The 'Sneintonite' before me, god bless his greasy cap and artistically stained black jeans, had clearly gone to the dogs a while ago. As he counted out change to purchase a generous bottle of cider I found myself beginning to wonder which of us were the happier.

Orwell's observation always suggested freedom to me, a freedom from rules and expectations and the responsibilities of day to day life. Indeed it's no surprise that that existence, on the cusp of destitution barely keeping ones head afloat, is viewed so romantically. Before deciding whether to chuck in the proverbial towel and join my cider drinking friend at the dogs I decided to spend a good seventeen minutes rifling through my book case to fully investigate the matter.

Case Study One

One of the problems with 'Down and Out in Paris in London' is that it blurs the line between fiction and non-fiction. Many of the events are undoubtedly Orwell's own however in an annotated copy to friend and critic Brenda Salkeld he confessed that certain elements 'are not actually autobiography but drawn from what I have seen'. Okay Georgie boy, so how much of the camaraderie and beauty of the Paris and London streets is made up then? Can I really trust your account? Also could you really have been completely destitute in Paris when Aunt Nellie was living around the corner? I don't think I'm ready to pack in the job just yet...

Case Study Two

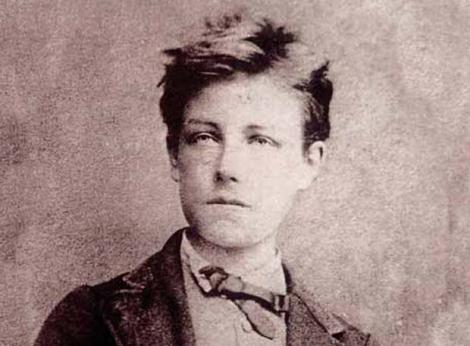

'And so off I went,fists thrust in torn pockets

Of a coat held together by no more than it's name.

O muse how I served you beneath the blue;

And oh what dreams of dazzling love I dreamed.'

Course you did Rimbaud, course you did. In 'Ma Boheme' Rimbaud appears to be laying down the blue print for every poetry drunk angel headed hipster that will follow him for the next century and a half. This idea of devotion to craft, to art, ahead of everything else is a romantic one. This lineage is particularly strong amongst the beat writers but I don't really trust those guys. They weren't destitute and suffering for their art. They were scoring chicks and having a blast. Unfortunately it was the same for Rimbaud, the poem was subtitled (fantaisie) after all and though he was famous for arriving in Paris on foot I don't think he bummed around too much whilst there. Still not quitting job...

The Final Case Study

John Fante was certainly down and out during much of his life. He is also the archetypal young male American writer drifting drunkenly through life hammering angrily at his type writer. It's all: rejection, booze, woman, booze, anonymous L.A hotel room, booze, rejection and although it makes for some great books (Ask The Dust is far superior to anything Bukowski ever wrote) it never sounds romantic or sentimental. Fante's stand in Bandini rarely sounds happy (cool sometimes for sure but not happy). My idealised life with my cider'd up Sneinton neighbour is further compromised by the fact that Fante had to dictate his final novel as his body, ravaged by alcohol, succumbed to diabetes which cost him first his eyesight then his life.

In conclusion- not quitting my job. Destitution is either a myth, a screen to score chicks and party or leads to death. It might make some great books but then I'm not planning on writing any. Also it's the holidays at the moment so bothered?